Answering the call to serve God’s people as a pastor, Emily Hollars Leitzke went right from college to the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg (Pa.), taking on nearly $60,000 in student loans.

“I kind of rationalized it to myself that when I had a call I would be making enough money to be able to pay those loans back,” she said.

Reality struck after her ordination in 2007 when the loan payments totaled nearly $1,000 a month under a 10-year payback schedule. On top of living expenses, it was too much.

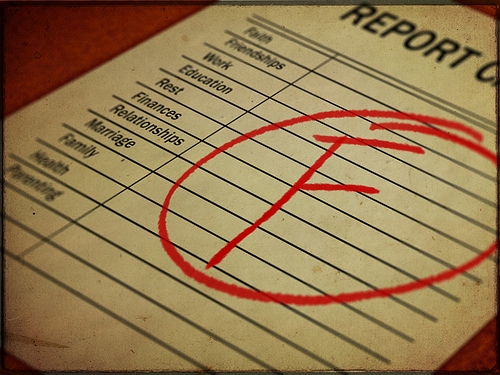

|

| ELCA pastors Emily and Tim Leitzke clip coupons to stay within a tight weekly budget and make monthly payments on Emily’s nearly $60,000 student debt. The Leitzkes and other ELCA clergy share a common burden: crushing student debt that is difficult to pay off on a pastor’s salary. |

“It took every last red cent of my income to pay everything but the loans,” said Leitzke, whose husband, Tim, was a pastor awaiting call (he is now in graduate school).

Leitzke’s predicament is common. Crushing seminary debt limits the choice of calls for the newly ordained, as well as the choice of pastors for smaller congregations. It places a financial millstone around the necks of pastors for years. Church officials fear cost may deter many qualified candidates.

The standard route for pastors is a four-year (three years of seminary tuition, plus one year of internship) master of divinity degree from one of eight ELCA seminaries. Tuition averages about $12,000 a year, and living expenses can bring the total cost above $100,000, according to the ELCA Fund for Leaders, an endowed seminary scholarship program (see “ELCA Fund for Leaders still premier vehicle,” below).

About 80 percent of ELCA seminarians take out student loans, said Jonathan Strandjord, director for seminaries with ELCA Congregational and Synodical Mission. In 2009, the average ELCA seminary graduate had $36,909 in student debt, he said, way above the $30,000 “threshold of concern.” In other words, such a debt will be difficult for a pastor to pay off.

The ELCA is mobilizing to help at every level: churchwide, synods, congregations, seminaries and affiliated agencies. Thanks to a $1 million grant from the Lilly Foundation, the church is coordinating a pioneering strategy, Stewards of Abundance, to reduce seminarian debt.

“Nobody wants pastors going out of the ELCA seminaries saddled with debt to the degree that it gets in the way of doing the ministry God has called them to do,” said Chick Lane, director of the Center for Stewardship Leaders at Luther Seminary, St. Paul, Minn., where the average graduate in 2009 had educational debt of $37,460. “There’s a lot of angst around this place about the level of student debt.”

In 2007, Luther developed a coaching program to help seminarians manage finances, avoid debt and become better stewardship leaders in their ministries. Students meet regularly with a volunteer finance coach to review the basics of budgeting, borrowing, interest and cash flow.

Financial coaching helped clergy couple Dane and Ingrid Skilbred, 2009 Luther graduates, who together have $90,000 in student debt, with $700 monthly loan payments. The couple also received help from the Northwestern Minnesota Synod, one of many with a debt-relief program.

Two years after graduation, they’re still using the notes and spreadsheet they worked out with their coach, Bill Roos, an accountant for H&R Block. “Financial coaching [helped us] completely face our debt,” Ingrid Skilbred said.

Working together

Luther‘s coaching model expanded to other ELCA seminaries thanks to the nonprofit Stewardship of Life Institute (SOLI), based at Gettysburg Seminary.

To work on stewardship education for future clergy, the institute cooperated with the ELCA Blue Ribbon Commission on Mission Funding to bring together the resources of the churchwide office, seminaries, Board of Pensions, and synods and their bishops. They developed “Competencies of a Well-Formed Stewardship Leader” (download at the ELCA website) an education strategy with financial coaching and training resources for rostered leaders.

The Stewards of Abundance project will accelerate efforts with a three-point strategy over three years:

• Financial and stewardship education at all eight ELCA seminaries.

• Scholarships for seminarians.

• Help in reducing the cost to students of seminary education.

Stewards of Abundance is also helping make the comparatively efficient ELCA theological education system more so. For example, perhaps more costs can be shared between schools, as in the case of Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary, Columbia, S.C., and Lenoir-Rhyne University, Hickory, N.C., which share a chief financial officer.

“Clearly you can’t just keep cranking costs up and expect scholarships to keep up,” said Donald L. Huber, Stewards of Abundance project director and a retired dean of Trinity Lutheran Seminary, Columbus, Ohio. As costs have risen, some funding sources have dried up, leading seminaries to raise tuition.

Stewards of Abundance is giving each seminary a matching grant of $12,500 to implement a stewardship education program. Most are adapting the SOLI financial coaching model to their needs.

At Pacific Lutheran Seminary, Berkeley, Calif., financial coaches and students use Skype and other Internet tools to do long-distance stewardship education, said Tom Rogers, a homiletics professor who leads the school’s coaching program.

“We don’t have, as Luther Seminary does, a thousand Lutheran churches within walking distance of the school,” Rogers joked.

Distance coaching is incorporated into SOLI‘s website, which allows coaches and students from all ELCA seminaries to log in, access documents, participate in blogs and talk via Skype.

Stewardship leaders

Financial coaches also try to help seminarians become better stewardship leaders in the parish.

“Most congregations talk about money as an area of anxiety — high anxiety,” said Jerry Hoffman, former director of Luther‘s Center for Stewardship Leaders and now a stewardship consultant. Helping future leaders become comfortable with finance can bring congregations out of anxiety and into “the joy of what it means to be a steward,” he added.

That approach worked for Christa Compton, a second-career seminarian at PLTS. “Money can be such a taboo subject, especially during these difficult economic times, and it is so often a source of conflict in congregations,” she said. “My coaches helped me grow more comfortable talking about money … and helped me to understand [it] as a gift that the church can use to live out the gospel.”

With so many initiatives focused on stewardship and reducing pastoral debt load, the ELCA hopes to foster a culture of generosity to assist pastors with their loans.

That would help pastors like Leitzke, who is paid about $10,000 below her synod’s salary guidelines and hasn’t had a pay increase in two years. When she couldn’t pay her student bills, she put the loans into emergency deferment until they could be consolidated with a longer payout date. The resulting $230 a month payment (due to climb under a progressive payback formula) is now more manageable, but the debt will be part of her finances for the next 25 years.

Leitzke is glad the whole church is rising to help. “We are called to be pastors of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America,” she said. “It’s a larger concern of the ELCA.

“This is where I’ve been called to be. God’s not done with me yet. We haven’t gone hungry; we’re not in danger of losing our house; the baby doesn’t eat that much. We’re going to be OK.”

ELCA Fund for Leaders still premier vehicle

Being a 2002 ELCA Fund for Leaders Scholarship recipient still makes a big difference for Meredith Lovell Keseley. “The scholarship has brought to life for me what it means to be ‘surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses,'” said the pastor of the Lutheran Church of the Abiding Presence in Burke, Va.

Keseley is grateful that she can focus on her ministry and family without the burden of debt. “I will never even know the names of the ‘witnesses’ who contributed to my scholarship, but I feel their presence, their prayers and their support,” she said.

The Fund for Leaders remains the ELCA‘s premier vehicle to ensure that the cost of theological education is not a hindrance to raising up church leaders. Approved by 1997 Churchwide Assembly with the goal of creating a permanent $200 million fund, today it stands at $30 million and growing.

“If you include this year’s class of recipients, it’s about 800 scholarships awarded,” said Donald M. Hallberg, interim director of the fund. “About $7 million has been awarded since the inception. So we’re doing well.”

The fund still has a long-term goal of raising $200 million to invest and provide scholarships that defray the cost of seminary as much as possible for as many people as possible, he said, adding, “This makes it possible for seminaries to recruit young people to be those courageous thinkers and leaders and pastors for the future of the church.”

Thanks to the Fund for Leaders, Kerri Wadzita, a second-year student at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg (Pa.), can focus on her studies, not her debts. “It’s been a wonderful blessing to be supported financially through [the fund] scholarship,” she said.

Reprinted from the November 2011 issue of The Lutheran magazine.

ey management and prevent credit card debt. It’s called spending less than one earns, and one magic ingredient makes this recipe for success work. It may sound simple, but as Trent notes, it’s a lot harder to do.

ey management and prevent credit card debt. It’s called spending less than one earns, and one magic ingredient makes this recipe for success work. It may sound simple, but as Trent notes, it’s a lot harder to do.